Table of Contents

Conversion Chart

We love formulas, don’t we. We convert currencies, units of measurement, and we software to convert complex digital files from one format to another. Nowadays we can even rely on software to translate languages back and forth instantly for us, and while it doesn’t always work great, it’s at least helpful.

So when it comes to eyesight, surely we can convert everything too!

I’m guessing you’re in one of two situations, if you’re looking to convert diopters and acuity.

Either:

- You have a glasses prescription and you want to know whether you have 20/40 or 20/200 vision, or

- You have an eye chart and you want to know what you prescription should be, based on what line you can read.

Ok, I’ll start out by appeasing you, and then I’ll tell you why it doesn’t work.

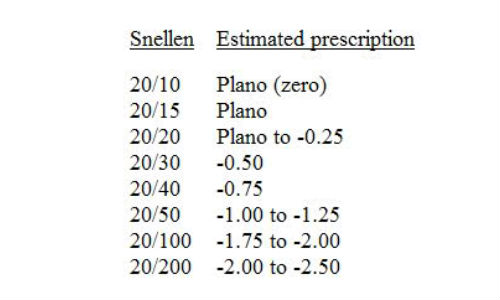

Some people have created believable-looking charts that match up diopters and acuity, such as this one for myopia:

| Prescription in Diopters | Acuity |

| -1.00 | 20/40 |

| -2.00 | 20/80 |

| -3.00 | 20/150 |

| -4.00 | 20/300 |

| -5.00 | 20/400 |

| -6.00 | 20/500 |

Well, all right, that sure looks helpful. And it’s not totally useless. For some people it will be about right.

For others, it will be way off.

For hyperopia, people often just try a few pairs of glasses on at the drug store and buy the pair that helps them read the book in their hands.

Converting these things are a bit like taking an average of how much weight a bodybuilder can lift based on his muscle size. There’s a relationship, but geez, there’s also some small guys with really dense, small muscles and an uncanny ability to pull a ridiculous amount of weight off the floor due to their training and muscle efficiency.

So it is with vision. Not so much to do with muscles, but the brain. Some other optical factors are at play too.

Here’s the problem. Diopters are an objective measurement. Here’s how it’s calculated…

Diopters and Blur

For glasses prescriptions, the diopters on your prescription such as -5.00 tells you how far your eyes can focus and therefore how much lens power is needed. It’s basically an inverse of the distance to your “edge of blur”. If you’re nearsighted and look at a sample of fine print and find that it begins to blur at 20cm away, your prescription would be -5.00.

When your eye doctor determines your prescription, he uses a test that measures the refraction of each of your eyes, which is how much the light is bent as it passes through your eye’s components and then onto your retina. This is done with a device called an autorefractor or retinoscope. It’s where you’re supposed to hold still and stare at something in the corner of the room. When the light is bent too much or not enough, and the light rays would come to a focus in front of or behind your retina, you would be myopic (nearsighted) or hyperopic (farsighted) and given the appropriate prescription.

The Subjective Test

Your eye doctor also does a subjective test, the old “which is better, #1 or #2?”. He sticks that huge thing on your face that you rest your chin on and look through the lenses. It’s called a phoropter. He flips different lens combinations in place in front of your eyes to see how you respond. I remember those. Half the time they looked the same, or they looked different but I couldn’t decide which was “better”, 1 or 2, so just picked one each time anyway after he flipped it back and forth several times and got impatient, or I insisted they were the same. Is that scientific? It always felt like a crapshoot to me.

What he’s doing, of course, is giving you two different prescriptions to look through to decide which one is better for you. It all depends on your responses. He flips through a whole series of them, with and without astigmatism correction, until he narrows down on a prescription that you seem to like best, and voila, that’s what you get.

The Visual Acuity Test

He might also have you just read the chart without anything on your face. This will be your 20/xx reading, such as 20/50, 20/80, 20/100, etc. Or if you can read 20/20, you don’t belong there at all.

The “20” part on the top of the fraction represents 20 feet. He may use mirrors to simulate the distance in a small room, but optically he’s always testing you at 20 feet. This is because focusing at 20 feet is pretty much the same as focusing at any farther distance, and 20 feet therefore can be considered “distance”.

In countries using the metric system, the first number will be “6”, for 6 meters. Same distance, roughly.

The bottom number, ie: the “40” for example in 20/40, may seem kind of convoluted but makes sense when you wrap your head around it. It represents the label on the smallest line you can read, which is labeled such because a person with “good” vision can read that line from that distance away. So if you can read the 40 line, your vision is 20/40, and a person with good vision should be able to read that line from 40 feet away, while you have to get up to 20 feet to barely read it.

As you may be learning at this point, this is all pretty rough, despite those convincing looking decimal points in a prescription like -4.25. That’s why they have to test your vision in so many ways, to kind of triangulate on a prescription because otherwise you often get a prescription that doesn’t work for you. Even then, sometimes it makes you dizzy and you have to go back two or three times to get a different prescription. Why do you suppose that is?

Converting the Numbers

The table I gave further above is one possible way to understand diopters and the 20/something acuity test.

But there’s a better way to understand it. The real answer isn’t convenient, but it’s much more hopeful as far as your potential for improvement.

Vision Changes

It’s extremely common for people to go from one eye doctor to another and be handed a different prescription.

Why?

When your vision is bad, everything makes a difference. Anything may make you more nervous or cause you to use your eyes more poorly, causing tension and defocus. The time of day, what you were doing today, your state of mind, not to mention things out of your control like the ambiance in the office, the eye doctor’s personality, the order in which he does the tests, the previous prescription he’s going off of… All these factors can change the result.

Granted, if you’ve been wearing glasses for many years, your eyes tend to get locked down with tension, and the tension doesn’t release often, certainly not when your vision is being tested, so the tests from one visit to another will probably lead to the same prescription or pretty close to it.

People who don’t regularly wear glasses, or have never worn them but are starting to experience blurry vision, such as children, or older people who are struggling for the first time to read up close, can get a whole range of inconsistent prescriptions.

The fact is, vision changes.

It changes over short periods of time. Minutes. Seconds. Conventional eye care doesn’t take this into account. It disrupts their models of how the eye works. And if it changes so easily, that means glasses are unnecessary and there must be a way for vision to get better without them more consistently. These cases are a nuisance to eye doctors who would rather believe that there is nothing to be done but give patients glasses (or perform surgery).

One thing I recommend to people working on improving their vision is to get an eye chart and hang it on the wall. They soon find that their vision sometimes improves out of nowhere, lasting a second, several seconds, or even a minute or longer. And then it keeps happening.

Understanding why this is happening is at the core of the approach I promise to reversing vision problems. When you know what is good and bad for your vision, and notice some subtle things that you had thought made no difference to your vision, you gain a new respect for how sensitive your eyes are to your thoughts, emotions and actions.

Is the Prescription Right For You?

If your vision can change so much, how much sense does a single prescription make that you are supposed to wear all the time? Not much. Your eyes have to basically create that amount of myopia or hyperopia in order to see clearly through the glasses. So you can see why glasses might keep your blurry vision locked into place. They confuse your brain. They teach you that your vision is operating exactly the way it’s supposed to and you just need “correction”.

When your vision gets tested, the stress or discomfort you experience at the doctor’s office will usually cause you to experience the worst vision you ever do. So not only are you getting a single prescription that only is good for that moment, but you’re also getting a prescription that is too strong for you at other times! Your system adapts to the glasses by de-focusing your eyes to create that level of maximum blur at all times. Not good, right?

To exacerbate the problem, it’s common for eye doctors to over-prescribe slightly. Say with -3.00 you can read 20/20 on the chart, but he might try bumping it up to -3.25 or -3.50 and see if you can read 20/15 or 20/10. They feel like they’re doing the right thing by giving you stronger glasses. It also stops you from coming back later to complain that the distance is just slightly blurry at night, for example. At night, or in other adverse conditions, you might be straining your eyes more in an attempt to see things, resulting in more defocus that would require a stronger prescription, while during the day perhaps the -3.00 would have been perfect. Once you adapt to these stronger -3.25 glasses, he’ll be ready to give you a pair of -3.50 glasses, and so on.

It’s unfortunate, but keep in mind he’s just providing a service that you’re asking for, in the best way he knows how. The best thing to do is to improve your vision and get out of this vicious cycle of stronger and stronger glasses.

get help on our Facebook Group!

I founded iblindness.org in 2002 as I began reading books on the Bates Method and became interested in vision improvement. I believe that everyone who is motivated can identify the roots of their vision problems and apply behavioral changes to solve them.