Section 2 of this article is a continuation from the previous blog post,

Orthodox Myopia Research: Blind Alleys and No Cure: Section 1. Introduction

Recent news articles about myopia have given the impression that vision research scientists are finally making some exciting new discoveries about the far too common affliction. Far from it. Instead of steps advancing forward and blazing new trails, the researchers’ strides have actually been on a circular path, arriving at conclusions and concepts that were originally posited back in the nineteenth century. Most researchers are likely completely oblivious to the roots of their profession, truly believing that they’re on to something original. The following are but three examples to suffice in our discussion:

i. Pressures, demands and long hours of school study impact myopia

An article in 2015 stated that modern research has discovered a trend whereby students who spend too much time indoors are at a high risk of developing myopia. “This is particularly the case in East Asian countries, where the high value placed on educational performance is driving children to spend longer in school and on their studies.”[4] Yet in 1813, eye doctor Georg Beer (Figure 2.1) made these emphatic statements:

[H]ow utterly destructive to the eyes of growing young people is the modern system of educational hot-house forcing … People hug the ill-understood principle that ‘children must be occupied all day long,’ and so, all the day long, as fast as one master leaves the room another comes in. Of reading, writing, language-learning, drawing, arithmetic, stitching, singing, piano and guitar-playing there is no end, till the tormented creatures are pale, feeble and drooping and become to such a degree short-sighted and weak-sighted …[5]

Also in 1813, London eye surgeon James Ware presented a paper to the Royal Society in which he stated, “Near sightedness usually comes on between the ages of ten and eighteen.”[6] He further noted that the problem seemed to manifest itself in the literate and educated elite. What was likely the first statistical record of myopia, Ware reported that at least thirty two out of one hundred and twenty seven students at one college in Oxford were myopic. The count was based solely on students using either spectacles or a hand glass (for one eye), not eye examinations, so there may have been more cases of myopia. In any event, a correlation between nearsightedness and the demands of education was thus postulated.

The mid-nineteenth century saw a large number of statistical studies undertaken in numerous European and Western countries to measure the incidence of myopia in schoolchildren. The consensus from the data was that myopia was somehow acquired in the classroom setting. Eyestrain from too much near work and excessive hours of study seemed to be the culprits. In 1883, Hermann Cohn, German professor of ophthalmology and a prominent researcher of his time, stated, “It is most certain that overworking the eyes [of schoolchildren] may lead to short sight in spite of the most favourable locale …”[7]

ii. Increasing high incidence rates of myopia a concern

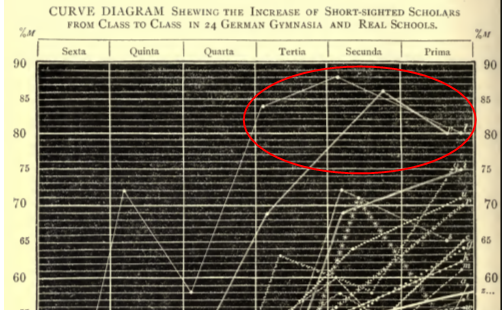

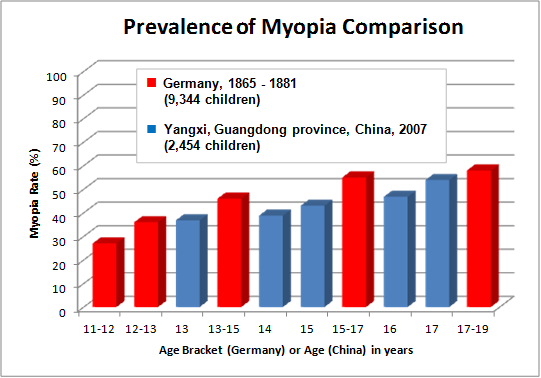

The same 2015 article further reported that up to 90% of Chinese teenagers and young adults are myopic.[8] Although this is certainly an alarming rate — indicative of an “epidemic” as one researcher stated — the upward trend comes as no surprise when you study vision science archives. In 1885, Burton Randall, an ophthalmic and aural surgeon based in Philadelphia, undertook a meta-analysis of the nineteenth century myopia research. The data included eye examinations from almost 150,000 students at various ages and levels of education. The results, published in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences, showed that Germany had a high incidence of myopia, with a rate as high as 77% for seven hundred and thirteen theology students at the University of Tübingen.[9] A few years earlier, Cohn had prepared a graph which included rates in the 80% to 88% range for senior level students at a couple of German schools (refer to Figure 2.2).[10] For a comparison of the average myopia prevalence in nineteenth century Germany at various school-age brackets versus that determined recently in a high myopia region of China, see the graph in Figure 2.3.[11]

The high incidence of myopia in Germany didn’t go unnoticed in the United States. In 1890, five years after Randall’s published work, eye doctors discussed the prevention of myopia at a medical association meeting in Louisville, Kentucky. The term “epidemic” wasn’t used, but the grave concern was stressed this way by one doctor: “Germany has become largely a nation of myopics, and l hope that will never be the fate of America.”[12] Another doctor echoed the sentiments by saying, “If there is not more done in the future than there has been in the past, I fear we will get into a condition like Germany. It is necessary for every physician to take this matter into consideration.”[13]

iii. Students should get outside for more sunshine

The latest supposed cutting-edge finding from vision science research is that students should spend more time outdoors in natural sunlight. Scientists aren’t sure of the exact reason why this is beneficial, but studies have shown that it helps reduce the risk of children developing myopia.[14]

Once again, when we scroll back in time, we find this very recommendation as a preventative measure. At the aforementioned 1890 medical association meeting in Kentucky, eye doctor Francis Dowling presented his paper entitled, “The Prevention of Myopia.” One of his recommendations was as follows: “Young persons, who may be predisposed to myopia, should never study at night time, all near work with the eyes should be done by good clear sunlight.”[15] For children already suffering from high degrees of myopia he had another more radical recommendation that would be considered laughable today: “In cases where the myopia is at all marked, all work with the eyes, such as study, etc., should be postponed until the sixteenth year. The child should, if possible, be sent to live in the country, where the range of vision is longer than in the city, and then it should be kept outdoors, in the fresh air, as much as possible.”[16] Bear in mind that, for most eye doctors of that era, healthy eyesight of children came first and foremost. If that meant sacrificing time spent in compulsory education, so be it.

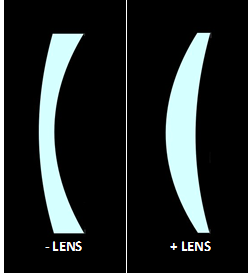

There is one particular idea in the nineteenth century that current vision scientists completely ignore, yet it is one they seriously need to revisit and study. That idea, which was widely held and debated among eye doctors, is that prescription eyeglasses are injurious to the eyes of children, causing further progression of myopia. In subsequent years, the negative effect of concave lenses (see Figure 2.4) in glasses was eventually coined optical poison.

Next Blog Post:

Section 3. Optical Poison Transforms Into Optical Elixir

[4] Elie Dolgin, “The Myopia Boom,” Nature 519 (19 March 2015): 277.

[5] G. J. Beer, Das Auge, Wien 1813, quoted in Hermann Cohn, The Hygiene of The Eye In Schools, trans. and ed. W. P.Turnbull (London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co., 1886), 215.

[6] James Ware, “Observations Relative to The Near and Distant Sight of Different Persons,” Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 103 (1 January 1813): 31.

[7] Cohn, The Hygiene of The Eye In Schools, 215.

[8] Dolgin, 276.

[9] Burton Randall, “The Refraction of The Human Eye: A Critical Study of The Statistics Obtained by Examinations of The Refraction, Especially Among School Children,” extracted from the American Journal of the Medical Sciences (July 1885): 23.

[10] Cohn, 72.

[11] Germany data in graph from Cohn, 69. China data in graph from Chen-Wei Pan, Dharani Ramamurthy and Seang-Mei Saw, “Worldwide Prevalence and Risk Factors for Myopia,” Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 32 (2012): 8.

[12] C.H. Hughes, comments to Francis Dowling, “The Prevention of Myopia: Read at the Sixteenth Annual Meeting of the Mississippi Valley Medical Association at Louisville, Ky., Oct. 9, 1890,”, JAMA 16, no.2 (10 January 1891): 45.

[13] C.W. McIntyre, comments to Francis Dowling, 46.

[14] Dolgin, 277.

[15] Francis Dowling, “The Prevention of Myopia,” 44.

[16] Ibid.

get help on our Facebook Group!

Doug is a retired civil engineer who improved his vision and wrote Restoring Your Eyesight: A Taoist Approach, a book about blending the Bates Method with the ancient principles of Taoism. He also contributes articles on vision improvement for New Dawn Magazine.